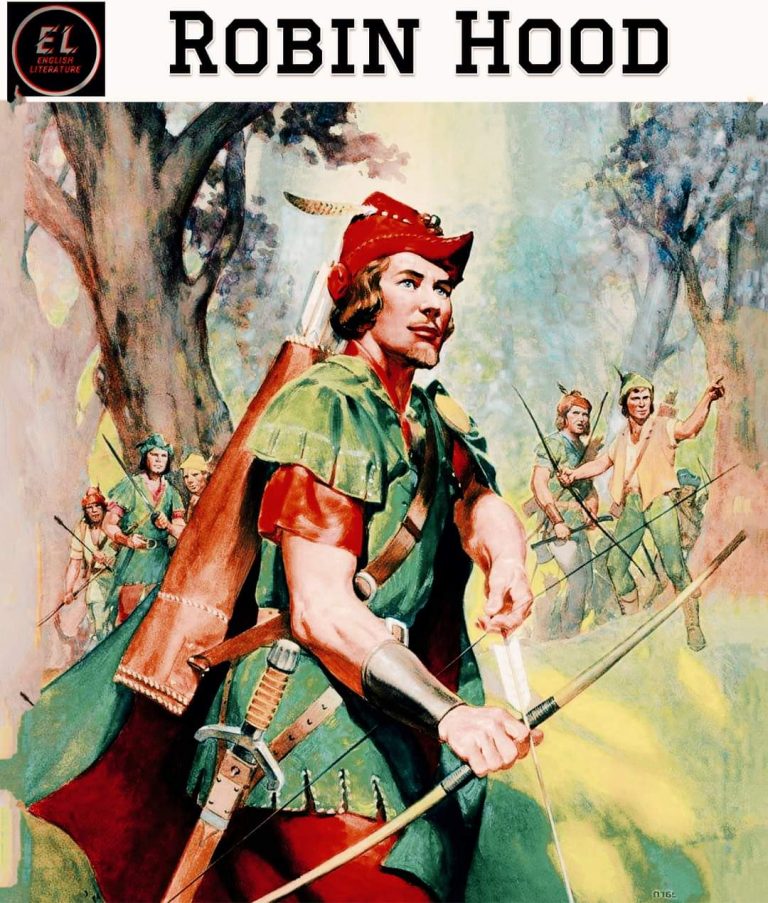

Robin Hood was the legendary bandit of England who stole from the rich to help the poor. The stories about Robin appealed to common folk because he stood up against—and frequently outwitted—people in power. Furthermore, his life in the forest—hunting and feasting with his fellow outlaws, coming to the assistance of those in need—seemed like a great and noble adventure.

Early Sources. The earliest known mention of Robin Hood is in William Langland’s 1377 work called Piers Plowman, in which a character mentions that he knows “rimes of Robin Hood.” This and other references from the late 1300s suggest that Robin Hood was well established as a popular legend by that time.

One source of that legend may lie in the old French custom of celebrating May Day. A character called Robin des Bois, or Robin of the Woods, was associated with this spring festival and may have been transplanted to England—with a slight name change. May Day celebrations in England in the 1400s featured a festival “king” called Robin Hood.

A collection of ballads about the outlaw Robin Hood, A Lytell Geste of Robin Hode, was published in England around 1489. From it and other medieval sources, scholars know that Robin

Robin Hood, the legendary thief of England, stole from the rich and gave the wealth to the poor. Stories about his life and adventures first appeared in the late 1400s.

Robin Hood, the legendary thief of England, stole from the rich and gave the wealth to the poor. Stories about his life and adventures first appeared in the late 1400s.

was originally associated with several locations in England. One was Barnsdale, in the northern district called Yorkshire. The other was Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire, where his principal opponent was the vicious and oppressive Sheriff of Nottingham. Robin’s companions included Little John, Alan-a-Dale, Much, and Will Scarlett.

The Robin Hood ballads reflect the discontent of ordinary people with political conditions in medieval England. They were especially upset about new laws that kept them from hunting freely in forests that were now claimed as the property of kings and nobles. Social unrest and rebellion swirled through England at the time the Robin Hood ballads first became popular. This unrest erupted in an event called the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.

Later Versions. By the 1500s, more elaborate versions of the legend had begun to appear. Some of these suggested that Robin was a nobleman who had fallen into disgrace and had taken to the woods to live with other outlaws. Robin also acquired a girlfriend named Maid Marian and a new companion, a monk called Friar Tuck. His adventures were then definitely linked to Sherwood Forest.

Beginning in the 1700s, various scholars attempted to link Robin Hood with a real-life figure—either a nobleman or an outlaw. But none of their theories have stood up to close examination. Robin was most likely an imaginary creation, although some of the tales may have been associated with a real outlaw.

Also at about this time, Robin began to be linked with the reigns of King Richard I, “The Lionhearted,” who died in 1189, and of King John, who died in 1216. The original medieval ballads, however, contain no references to these kings or to a particular time in which Robin was supposed to have lived.

Later versions of the Robin Hood legend placed more emphasis on Robin’s nobility and on his romance with Marian than on the cruelty and social tension that appear in the early ballads. In addition to inspiring many books and poems over the centuries, Robin Hood became the subject of several operas and, in modern times, numerous movies.

Tales of Robin Hood. One of the medieval ballads about Robin Hood involved Sir Guy of Gisborne. Robin and his comrade Little John had an argument and parted. While Little John was on his own, the Sheriff of Nottingham captured him and tied him to a tree. Robin ran into Sir Guy, who had sworn to slay the outlaw leader. When they each discovered the other’s identity, they drew their swords and fought. Robin killed Sir Guy and put on his clothes.

Disguised as Sir Guy, Robin persuaded the sheriff to let him kill Little John, who was still tied to the tree. However, instead of slaying Little John, Robin freed him, and the two outlaws drove off the sheriff’s men.

Another old story, known as Robin Hood and the Monk, also began with a quarrel between Robin and John. Robin went into Nottingham to attend church, but a monk recognized him and raised the alarm. Robin killed 12 people before he was captured.

When word of his capture reached Robin’s comrades in the forest, they planned a rescue. As the monk passed by on his way to tell the king of Robin’s capture, Little John and Much seized and beheaded him. John and Much, in disguise, visited the king in London and then returned to Nottingham bearing documents sealed with the royal seal. The sheriff, not recognizing them, welcomed the two men and treated them to a feast. That night Little John and Much killed Robin’s jailer and set Robin free. By the time the sheriff realized what had happened, the three outlaws were safe in Sherwood Forest.

Robin Hood’s role as the enemy of the people who held power and the protector of the poor was clearly illustrated in lines from A Lytell Geste of Robin Hode. Robin instructed his followers to do no harm to farmers or countrymen, but to “beat and bind” the bishops and archbishops and never to forget the chief villain, the high sheriff of Nottingham. Some ballads ended with the sheriff’s death; in others, the outlaws merely embarrassed the sheriff and stole his riches. In one ballad, the sheriff was robbed and then forced to dress in outlaw green and dine with Robin and his comrades in the forest.

The Death of Robin Hood

Legend says that Robin Hood was wounded in a fight and fled to a convent. The head of the nuns there was his cousin, and he begged her for help. She made a cut so that blood could flow from his vein, a common medical practice of the time. Unknown to Robin, however, she was his enemy. She left him without tying up the vein, and he lay bleeding in a locked room. Severely weakened, he sounded three faint blasts on his horn. His friends in the forest heard his cry for help and came to the convent, but they were too late to save Robin. He shot one last arrow, and they buried him where it landed.

Over time, the image of Robin as a clever, lighthearted prankster gained strength. The tales in which he appeared as a highway robber and murderer were forgotten or rewritten.